Cincinnati: Over Two Decades

of Immersion Education

The ACIE Newsletter, February 1999, Vol. 2, No. 2

By Norma Kearney, Program Facilitator, Foreign Language Academy at Heinold, Cincinnati, Ohio

|

As we move into the global society of the new millennium at an incredibly fast pace, due to the magical web of technological communications that takes us around the world at the touch of key, it appears that awareness of the importance of foreign language education has increased at an equally rapid pace. Those of us who have been involved in foreign language instruction, and especially in immersion education for a number of years, see this as an opportunity that we shouldn't ignore. Teaching a foreign language in a meaningful and practical way has been the goal of many programs for a long time. Now, due to an increasing interest in creating a multicultural and global environment in schools, circumstances are more favorable than ever for the development of new immersion programs and the improvement of existing ones. I am thrilled that the ACIE newsletter, CARLA, and the institute staff whom I had the pleasure to meet at this past summer's institute have offered us this opportunity and medium to get to know each other, learn from each other's experiences, and promote one of the most precious gifts we have been endowed with: human communication. The Foreign Language Academy at Heinold houses one of the magnet programs of the Cincinnati Public Schools in Ohio. The Academy, a "spin-off" of the Foreign Language Magnet Program conceived by Mimi Met in the 1970's, serves predominantly minority students from kindergarten through eighth grade. Any student living within a specific area may apply to the program, which offers the choice of French or Spanish as the immersion language. This offers an opportunity for all children to be in the program, and because there is no prior screening, also presents a potential challenge to staff members who must immerse the students regardless of ability level. Classrooms typically represent a wide range of abilities and while that is challenging in any classroom, it is especially so in an immersion classroom.

Of course, open admission is not the only challenge that we face. As many involved in this type of program know, the availability of committed teachers with a dual certificate (elementary education and foreign language), lack of immersion specific teacher training, and the need to document achievement through proficiency standards in the target language are some of the issues that we encounter on a regular basis. We have the good fortune to count on an enthusiastic staff and a principal, Nélida Mietta-Fontana, who honestly believes in teaching a second language in a meaningful way and who has been with the program as teacher, supervisor, and now principal. Heinold reflects diversity even in the physical set-up. In order to promote unity among the two language immersion programs, both are housed in one building. The staff is organized into teams, each composed of two English teachers, one Spanish teacher and one French teacher. Let's take a closer look at Heinold now.

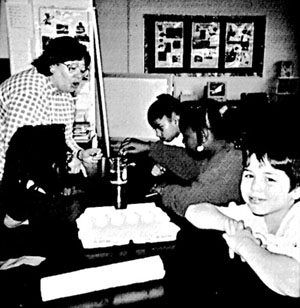

One of our veteran teachers, Carmen Reusing, knows very well that working in the program offers not only many challenges but numerous rewards as well. Carmen teaches third grade Social Studies, Science, and Math reinforcement in Spanish. She says that striving to accomplish district requirements through a second language, gain parents' trust, adapt the curriculum without compromising its quality, work with a highly diverse community of children in terms of abilities and backgrounds, and serve all students' needs are some of these challenges. Carmen feels rewarded when she sees the steady progress students make in the immersion environment, as compared with her experience in a more traditional foreign language learning environment. She is proud to contribute to the creation of an international environment which provides children with an understanding of other cultures. Carmen starts her content lessons by building the vocabulary that students will need for a particular unit. Her chalkboard is always very organized and students know that they will find the list of new words for the week on the left side of the board. For the lesson "Comunidades: Diferencias, similaridades, e interacciones entre comunidades rurales y urbanas" (Communities: Differences, Similarities, and Interactions between Rural and Urban Communities) Carmen has prepared a list of new words which students will use in sentences orally and in writing. Using the textbooks Ciudad y campo (Scott-Foresman; Schreiber, Stepien, Patrick, Remy, Gay, & Hoffman; 1984) and De radiante mar a mar (Houghton Mifflin; Armento, Nash, Salter, Wixson; 1992) and incorporating literature from different sources, students find the applications for the vocabulary learned. In this case, students will read, with Carmen's guidance, "El ratoncito de la ciudad y el ratoncito del campo," an Aesop's fable found in Escaleras Lectura (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich; Barrera, Canales, Rosenberg, Villarreal; 1987). Carmen then prepares a summary of the lesson which she writes on the blackboard. The summary remains on the board for at least two days, or until the students become familiar with it. Using the information provided, students now move to a written questionnaire which is used both as a comprehension check and an assessment tool. Connections among textbooks, classwork, and additional literature are constantly established. Using graphic organizers such as Venn diagrams, students are asked to represent differences and similarities between urban and rural communities. This activity also serves to assess students' ability to use the acquired vocabulary. The incorporation of culture is always present. For this lesson, Carmen discusses with students differences and similarities between a Spanish-speaking community and their own. She uses numerous sources, such as transparencies, videos, posters, and other audiovisual materials to help students acquire the concepts. Using graphic representations with a simple text, students make individual booklets to take home and share with parents. Observing Jacinte Lytle's French immersion class is another treat. With the use of lots of energy, hands-on activities, and wit, Jacinte delivers a science lesson on kinetic energy to a group of fourth graders. Every lesson becomes an opportunity to review previously learned concepts and vocabulary. Jacinte understands, as many immersion teachers do, that interaction among students is a necessary tool for language development. Students take turns demonstrating the results of their experiments to each other. In Jacinte's classroom, even math class becomes a language class! Next door in the Spanish immersion fourth-grade class, students are learning a science lesson on density (photo, p.11). Vicky Richter, who has been in the program since its inception, uses a lot of repetition, memorization, and dramatization to build the necessary vocabulary. As in Jacinte's class, students move around the classroom and interact using the target language. Every lesson becomes a language lesson. Students take notes and write sentences in their notebooks that later on will be shared. Next, they prepare a summary of the lesson for their personal science journals. Journal samples will be incorporated into the district's portfolios for the particular subject. Students are encouraged to share their work at home. In keeping with district standards, parents are asked to sign a note verifying that they've had an opportunity to participate in their children's school experiences. As in every immersion situation, physical demands and pressure to meet district requirements are constantly present. As a culmination of our program, students are offered the opportunity to travel to France or Spain in the eighth grade (depending on the language of instruction). Unfortunately, because of the costs involved, not many students get to travel. We are always exploring new possibilities to offer more students this invaluable opportunity. |