Can First Grade Immersion

Students Write

in the Target Language?

The ACIE Newsletter, May 2006, Vol. 8, No. 3

By Mary Carmen Bartolini, First Grade Teacher, Adams Spanish Immersion, St. Paul, MN

In 2003 the staff from Adams Spanish Immersion Magnet School was invited to participate in the Saint Paul Public School’s Project for Academic Excellence. One of the main elements of the project is the Literacy Initiative, which includes a daily one-hour Writer’s Workshop integrating reading and writing. During the workshop time, students adopt the life of a writer. They write every day, generating their own ideas and working through the writing process (draft, revise, edit, and publish). They are exposed to different genre studies and authors. They learn about the techniques authors use to draw readers in, to sustain their interest and ensure their understanding, to create tension, and to bring writing to a close. They analyze texts, thus learning how to vary sentence structure, embed essential details, or organize an argument. They use authentic literature as a model for their own writing. And, finally, they publish at least ten polished pieces of writing each year.

The district offers teachers a three- part professional development

institute on implementing the Writer’s Workshop, and

I was eager to take part. However, as I began the first level

of the training, many questions arose:

- How do I implement these ideas in an immersion setting?

- How can I write stories with children who are beginning to acquire vocabulary in a second language?

- What is the best sequence for developing this process?

- When am I going to teach the mechanics of writing?

- How can I find authentic books in Spanish that are good examples of different genres? How will I find the money to obtain the books?

- How much time is this going to take? •What if I spend all the time required and don’t see results?

- What about students who can’t write yet?

- How can I include an hour lesson in a traditional Language Arts block? How am I going to organize reading time in the schedule?

- What do they mean by “Students work to polish at least ten original pieces of writing each year?” Who determines when the piece of writing is ready to publish? Do they want perfect work? Do I have to type the stories and correct all the mistakes before placing the writing on the walls? Is that real student work?

Writer’s Workshop – Year One

In my initial attempts to implement ideas from the training,

I felt insecure and alone since no other first grade teacher

in my building had attended the professional development institute.

My students were sharing ideas in English most of the time

or were relying on theme-based prompts from our social studies

or science units to write simple pattern sentences. They were

not developing their own ideas — one of the goals of

the Writer’s Workshop. Nevertheless, with further training

and a chance to observe classrooms where the Writer’s

Workshop was being used effectively, I began to incorporate

the recommended sequence of study: the “writerly life”,

personal narrative, literary non-fiction, and poetry. Reading

authentic Spanish literature helped us develop ideas for our

writing, and we spent time sharing those ideas orally. When

it was time to write, the process went more smoothly.

Writer’s Workshop – Year Two

I finished the last phase of the professional development

institute and began the second year of implementation by assigning

a physical space for meetings, for writing materials, and

for the display of our work and by establishing a specific

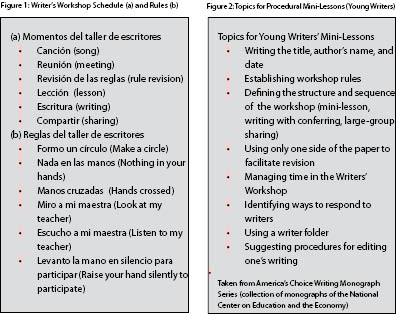

time for the daily workshop (see Figures 1 and 2, p. 7). The

consistency of the routines and the stability of the physical

spaces provided the kind of scaffolding that helps students

focus on learning and, in an immersion classroom, on second

language acquisition (Peregoy & Boyle, 2005).

Although most of the sharing during the first unit was in

English, little by little students started using words from

the books I had chosen to guide our conversations and develop

new vocabulary. I also took advantage of the books to work

on comprehension skills and to show my students cultural differences

when the books lent themselves to such comparison. Following

my modeling, students shared their stories with peers. They

gradually built up and used their Spanish, a key aspect to

developing oral language proficiency in the second language

(Cloud, Genesee & Hamayan, 2000).

My first grade students needed a lot of encouragement in their

initial attempts to write. However, they were so completely

involved in the process they overcame their fears. Students

started using the vocabulary I had introduced during writing

time (escritor, escritora [writer], reunión [meeting],

lección [lesson], ideas [ideas], ¿Quieres compartir

conmigo? [Do you want to share with me?], Me gusta tu historia.

[I like your story.], etc.). They learned the routines and

the language that goes with them. As a result, their second

language development was being supported (Peregoy & Boyle,

2005).

Students began to collect entries in their writing folders.

Their ideas came from the books we read, from classroom experiences

(field trips, projects, presentations), and from their personal

lives (weekend activities, birthday parties, visits to relatives).

They wrote classroom books to reinforce the idea of themselves

as writers. These were the most requested books from our classroom

library during independent reading time.

Each student brought in a memory box to establish his/her

“writerly life.” Serving as a connection between

school and home, parents and children enthusiastically created

the memory boxes choosing special objects that reflected important

moments in each student’s life. After sharing the stories

that came with each object we started to write following the

steps of the writing process. It was a powerful experience

for my students because they were free to choose their own

topics (Peregoy & Boyle, 2005) and they were taking responsibility

for their own learning.

After working on their pieces for several days, we created

a checklist to assess our final products. Using the checklist

students were able to examine their own writing to ensure

that they had all the elements of a finished piece.

Writing in a Second Language

Current studies confirm the similarity of the writing process

for both first and second language writers: “…

The problems writers face are either specific to the conventions

of writing English, such as spelling, grammar, and rhetorical

choice, or they relate with more general aspects of the writing

process, such as choosing a topic, deciding what to say, and

tailoring the message to the intended audience— elements

that go into writing in any language” (Peregoy &

Boyle, 2005, p.208). Although the writing process is similar

for both first and second language writers, there are important

differences. Second language writers have a more limited ability

to express original ideas since they do not possess the depth

or breadth of vocabulary, the understanding of idiomatic expressions,

or the ear for correct grammar usage that native speakers

do. Nor do they have much exposure to writing in the target

language. For this reason it is crucial to give students many

different opportunities to write in order to improve their

writing and promote second language acquisition (Peregoy &

Boyle, 2005).

The Writer’s Workshop, an example of the process approach

to writing, places the learner at the center of the learning

process and considers that children learn to write most successfully

when they are encouraged to start with their own expressive

language. This approach affirms research findings: writing

should take place frequently and within a context that provides

real audiences for writing (Gibbons, 2002).

After completing the professional development institutes and

implementing the Writer’s Workshop in my first grade

immersion classroom, I have found some answers to the questions

I inititally posed. They appear below.

| How do I implement these ideas in an immersion setting? | The Writer’s Workshop is related to the process approach to teaching writing that has been used successfully in second language classrooms. Establishing the rules and routines for the workshop are important in creating a solid base upon which to build future learning experiences. |

| How should I write stories with children who are beginning to acquire vocabulary in a second language? | Students start the year sharing stories orally using their first language but increase the use of the immersion language after acquiring vocabulary from books and class routines. Teacher modeling of the immersion language helps students develop their language skills. |

| What is the best sequence for developing this process? | The Writer’s Workshop scaffolds a complex process by breaking it down into smaller steps (pre-writing, drafting, revising, editing, and publishing). From the beginning students develop vocabulary and writing ideas from exposure to authentic literature. |

| When am I going to teach the mechanics of writing? | At first writing time is shared with skill-development time; later, the whole hour is dedicated to the writing process. |

| How can I find authentic books in Spanish that are good examples of different genres? How will I find the money to obtain the books? | One of the best ways to find appropriate books is to go through personal collections identifying books that are examples of each genre. Share ideas with colleagues, ask for their advice and expertise, analyze books together. Tell parents about the Writer’s Workshop, propose a list of books and ask for donations of books or money to buy books. |

| How much time is this going to take? What if I spend all the time required and don’t see results? | The implementation of the Writer’s Workshop in an immersion classroom will take more time and effort than in a monolingual classroom, but the benefits are numerous: Students take ownership of their own writing; they understand the process and can concentrate on each phase; their second language skills increase daily with exposure to authentic literature and class routines. |

| What about the students who can’t write yet? | Oral language development is an important pre-writing stage that is achieved by reading and discussing different genres of literature, talking about personal experiences inside and outside the classroom and managing class routines. Schedule the Writer’s Workshop when an assistant may be available to help with struggling writers. |

| How can I include an hour lesson in a traditional Language Arts block? How am I going to organize reading time into the schedule? | Since the Writer’s Workshop is built on an interaction between reading and writing, the Language Arts block encompasses both. Reading authentic literature immerses students in the study of genres and promotes the development of oral language proficiency. Strategies and skills learned during both writing and reading can be integrated and used with other subject areas like science and social studies. |

Who determines when the piece of writing is ready to publish? Do I have to type the stories and correct all of the mistakes before placing the writing on the walls? Is that real student work? |

Students, with direction from the teacher, develop rubrics or checklists to assess their own and peers’ writing. Self and peer editing is part of the writing process. |