Why Bother with Immersion Language Proficiency Assessment?

The ACIE Newsletter, February 2006, Vol. 9, No. 2

By Maria Alicia Arabbo, K-12 Spanish Immersion Program Coordinator, St. Paul Public Schools, St. Paul, MN

Is immersion programs thrive across the nation the need to carefully assess and thoughtfully reflect on how immersion students’ language develops across grade levels becomes more pressing. In the St. Paul Public Schools (MN), a program-level proficiency assessment initiative has helped our K-12 Spanish immersion program gain valuable information on students’ immersion language skills. This, in turn, is allowing us to reconsider program design and encourage pedagogical practices that can better address

The Saint Paul Public Schools district first brought language

immersion education to Minnesota back in 1986. Adams Spanish

Immersion Magnet School was initially developed as an early

total immersion program and began with 44 K-1 students and

two teachers. In 1993, the program was articulated to the

secondary level at Highland Park Junior High and in 1995 articulated

to the upper secondary level at Highland Park Senior High.

Today, the K-12 Spanish Immersion Program’s enrollment

boasts 913 students and 47 teachers across the three school

sites.

In 2003, the program was awarded a federal Foreign Language Assistance Grant (FLAP). One of the goals of the grant was to establish a comprehensive annual assessment of students’ Spanish proficiency by testing at specific grade levels. Up until that time, due to a lack of resources, the program had been unable to articulate a holistic system for immersion language assessment, one that attended to students’ abilities in reading, writing, listening and speaking across the K-12 spectrum. To ensure students’ continued progress with the language proficiency goals of our program and identify specific areas of weakness in language learning, we believed a comprehensive assessment framework targeting students’ language development over time had become imperative. Best practice in second language education tells us that a long-term, sustained commitment to language learning within an effective program is essential if the program seeks to develop higher levels of proficiency.

Assessment Task Force

As a first step, an assessment task force was established

to explore, make recommendations, and develop a well thought-out

plan, including goals and a timetable for implementation.

The primary goal at the beginning of the task force’s

work was to define beliefs and find common ground around assessment

in order to develop an inclusive atmosphere in which participants

could feel ownership of the work. The task force members researched

assessment instruments used at different immersion programs

around the country and collected samples for review and possible

adaptation. We then considered issues of cost, full implementation

coordination, parent support, and data management. As a result

of the task force’s work, a plan to systematically gather

data on Spanish language proficiency development in the areas

of listening comprehension, speaking, reading and writing

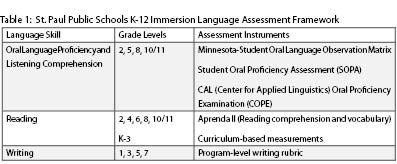

was created (see Table 1, p. 7 for overview of assessment

plan).

We are currently in our third and final year of funding.

Year I focused mainly on the development of the framework,

Year II on teacher preparation and piloting of the oral language

and reading assessment tools, and Year III efforts include

the co-construction of a program-level writing rubric and

implementation of the entire assessment plan. As a program

we have learned a great deal from this initiative. Observing

what students do with language, determining what they have

learned as well as how well they are learning it, identifying

commonly occurring errors in verbal expression and understanding

them as indicators of target areas for further communicative

development are just some of the valuable insights gained

from this experience.

The comprehensiveness of our assessment plan has provided the program with a more complete picture of students’ language progress. Overall, results have indicated that the majority of our immersion students are successfully acquiring intermediate-high to advanced levels of proficiency by grade 8. One participating teacher shared that the assessment process and results have helped her to think more purposely about planning for students to talk to each other in Spanish. As Pauline Gibbons argues, “central to the notion of assessment is the principle that the information it provides should be used to inform subsequent teaching and learning activities.” (Gibbons, 2002, p. 123)

The assessment framework we have designed is fulfilling its

purpose. It is raising teacher awareness of student proficiency

and informing curriculum and instruction. We encourage other

immersion programs to make a similar commitment to analytically

tracking their students’ language development. Collectively

then, we can begin to pool these data and establish much-needed

benchmarks for the immersion student audience. So, why bother

with immersion language proficiency assessment? Because the

time invested is highly compensated by the depth of information

we obtained on our program-level performance.